Besides making a variety of great cameras over the years, the Pentax company also holds the distinction of making the smallest interchangeable lens SLR, as well as one of the biggest. The former being the Pentax Auto 110 – the latter being the mammoth Pentax 67. And while the Pentax 67 has had a long and successful life (still being in production as late as 2012), the beautiful potential of the Auto 110 never really came to fruition as a result of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Imagine yourself back in the ’70s. You enjoy photography, and you love your Minolta XE-7 35mm camera. You love its flexibility in accepting different lenses and flashes. You love the bright viewfinder which makes easy work of accurate focusing. But, you’re not terribly fond of having to carry around a big bag of gear. What you need is is a “Dr. Shrinker” shrink-ray (I’m dating myself here) to get that SLR down to a manageable size. And if you were successful at obtaining said weapon, you’d be left with something like the Pentax Auto 110. It’s a full-fledged interchangeable lens SLR “system” that made use of the popular 110 cartridge film – a fact that led to its demise as well as its reason for being.

By the time the Auto 110 hit the market in 1979, 110 film had been around for seven years. And during that time it was steadily building a reputation of mediocrity. It’s not that it didn’t have its share of shining moments – think the Minolta 110 Zoom SLRs, Rollei A110, and 110 Kodachrome – but most of the cameras that were made to use this film were cheap and crappy. That’s the best way I can say it. And when you put tiny film in a crappy camera, you can only get crappy results. The graphic to the right is a life-size example of the size of a 110 negative.

In advertisements of the day it was stated that this film could be successfully enlarged not only to 5×7 or 8×10, but even to 11×14. I think that would have had to be under the very best of all conditions. But the very pocketable-ness of the cameras that used the film made us buy them and take them on vacations and weekend outings. And they were simple and cheap enough for the kids to use. The first camera I had as my very own was bought at K-Mart and took 110 film. I still have it, of course. But the point is that image quality from cameras that shot this film was less than stellar. And by the late 1980s use of 110 film was dwindling. Still, between 1979 and 1985, Pentax owned the upscale 110 camera market.

The major feature that keeps me from referring to the Auto 110 as “pro-oriented” is the lack of any manual control over shutter speed or aperture. It is a fully automatic camera. But the sophistication of its automation was certainly cutting-edge. The camera’s lenses had no aperture mechanism. Instead, a combination iris/shutter is mounted in the camera body with programmed shutter speeds ranging from 1/750th sec to 1 sec. And the f/stop range is from f/2.8 – f/13.5. The camera requires two button-cell batteries to operate and uses center-weighted TTL metering to set the exposure. But, despite being fully automatic and using tiny film, this camera is a lot of fun to use. It will also attract a lot of “what the heck is that?” from people around you.

The first surprise you find is how bright the viewfinder is. You have no trouble seeing the image. There is no micro-prism collar, but the split-image focusing spot is excellent. Pressing the shutter release halfway will yield either a green or red light in the viewfinder. If it’s green, you’re good to go. If it’s red, you’ll need to find a way to steady the camera because the shutter speed is deemed too long.

The film advance lever requires two strokes to advance the film to the next frame. But the sound it makes when winding is so crisp that you’ll want to do it twice. It feels like the precision instrument that it is. But the real selling point of this camera system is the ability to change lenses.

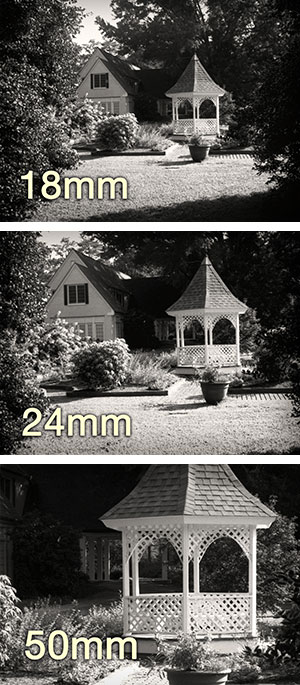

The standard lens is the 24mm. But two other lenses that are available are the 18mm wide-angle, and the 50mm telephoto. And man, do I love that 50mm! What reach. It’s perfect for portraits. The 18mm however, is only slightly wider than the standard lens, and I found limited use for it. But I guess if you need a little more room in your shots it fits the bill. It also seems a bit harder to focus – just as any wide-angle lens would be, so I guess that can’t be a con. The lenses have wonderfully large focusing rings that make them easy to grip. And they have distance scales marked in both feet and meters.

The camera system also had two different flash units available. Mine came with the AF130P. The flash screws in to a unique sync terminal. There is no traditional hot shoe or PC connection, so using flashes other than the two made for this camera is not possible. I attempted to use the flash outdoors as a fill-flash for a portrait. But the results were about three stops overexposed. I read afterwards that when the flash is mounted the shutter speed sets to 1/30 sec – which is a little slow for outdoor work and explains the overexposure bit. Unfortunately, I shot up my two rolls of Lomography Orca 110 film before I tried to use the flash indoors. So, I’ll save that for later and update this post when I do it.

Pentax updated this camera to the Auto 110 Super in 1982 – and even added more lenses to the line-up before they ceased production in 1985. By then, the 110 format was losing footing in the market – mainly due to the quality of the images it produced. If more photographers had been using this Pentax system, though, my bet is that it would have hung around a little longer.

So what’s my take on this little gem of a camera system? Well, it has a very high coolness factor – especially when you change the lenses. People will want to know what you have. They’ll want to hold it because it’s so damn cute. Its bright viewfinder makes it easy to focus. And the sharpness of the lenses is pretty impressive.

My biggest gripe is that film for these cameras is expensive – the Orca 100 I shot for this project was about $7.50 per cartridge. But I’m thankful to Lomography for keeping this format of film alive. Their color 110 film is about the same price.

Processing the 110 film posed a certain challenge, as I had no experience with doing so prior to this. I ended up with an old Trumpf JOBO tank whose reel could be adjusted for 35mm or 16mm. And since 110 film is the same physical size as 16mm I was set.

I did, however, manage to put several long scratches down the first roll I developed by pulling it out of the cartridge too carelessly. I did much better on the second roll. Check out the photos following the camera specs.

Technicals Specifications:

Original List Price (1979): $249.00 (w/24mm lens, case, and strap)

Price in 2015 Dollars: $816.00

The two additional lenses were each $68.00. That’s $225 in today’s money. And the flash was $42.00 ($137.00)

Manufacturer: Pentax

Model: Auto 110

Year Introduced: 1979

Film Format: 110 Cartridge

Lenses: 24mm 2.8, 18mm 2.8, 50mm 2.8

Eventually there would be a 70mm 2.8 and a Zoom lens added to the line-up.

Shutter: automatic aperture/shutter combination

Self-timer: No

Shutter Speeds: 1/750th to 1 second

Shutter Release: on top

F/Stops: Automatically set between f/2.8 – f/13.5

Built-in Meter: TTL Centerweighted

Film Speed/ASA Range: 100 or 400 only – set via tab on film cartridge

Flash Sync: non-standard connection terminal

Film Advance: double-stroke lever on top

Frame Counter: On films backing paper, visible through window on back

Double-exposure capable: No

Finder: Bright with green/red exposure indicator lights

Mirror: Yes

Other points of note: Hinged back, tripod socket

All text and photographs on this website (other than found-photography and otherwise noted) are © 2014-2021 Steven Broome. All rights reserved.

I was always wondering about those camera, actually looks pretty good!

LikeLike

I was surprised, too! And a lot of fun to use.

LikeLike

Hey,mister steven.I’m glad because i have one with the complete set and i want to sell it.

LikeLike